Git Rebasing

- Views

In Git, there are two main ways to integrate changes from one branch into another: the merge and the rebase. Let’s see what rebasing is.

The Basic Rebase

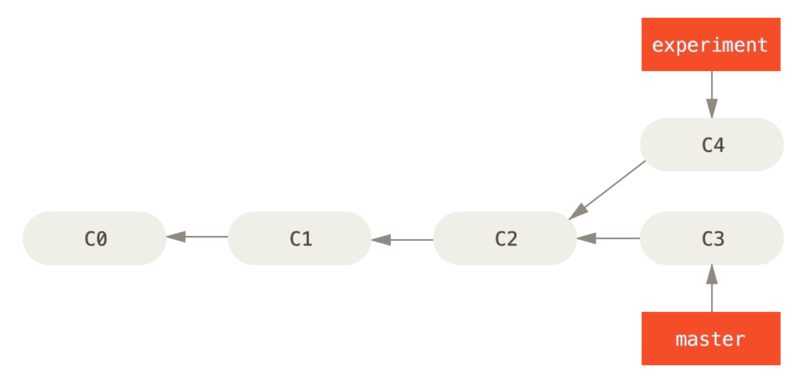

Like the earlier example from Basic Merging, you can see that you diverged your work and made commits on two different branches.

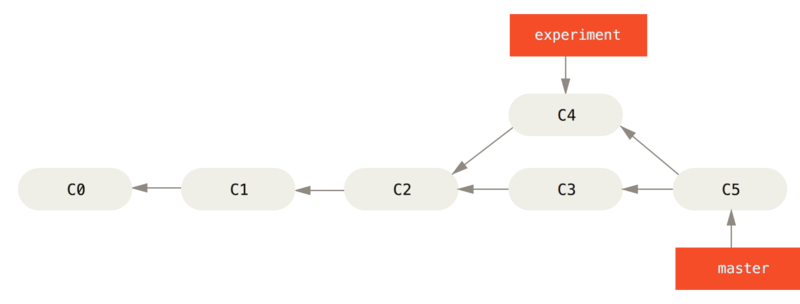

The easiest way to integrate the branches, as we’ve already covered, is the merge command. It performs a three-way merge between the two latest branch snapshots (C3 and C4) and the most recent common ancestor of the two (C2), creating a new snapshot (and commit).

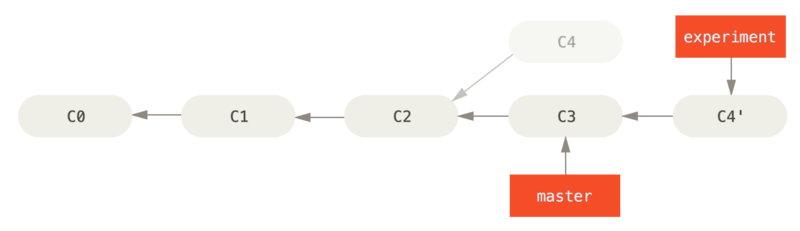

However, there is another way: you can take the patch of the change that was introduced in C4 and reapply it on top of C3. In Git, this is called rebasing. With the rebase command, you can take all the changes that were committed on one branch and replay them on another one.

In this example, you’d run the following:

$ git checkout experiment

$ git rebase master

It works by going to the common ancestor of the two branches (the one you’re on and the one you’re rebasing onto), getting the diff introduced by each commit of the branch you’re on, saving those diffs to temporary files, resetting the current branch to the same commit as the branch you are rebasing onto, and finally applying each change in turn.

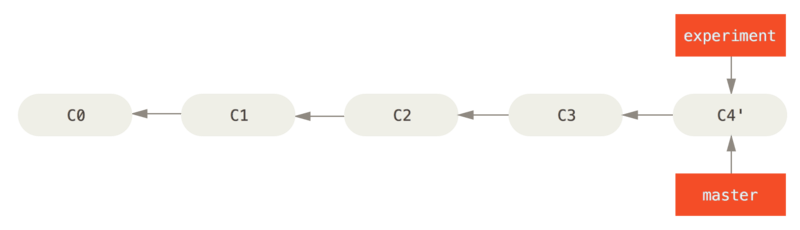

At this point, you can go back to the master branch and do a fast-forward merge.

$ git checkout master

$ git merge experiment

Now, the snapshot pointed to by C4’ is exactly the same as the one that was pointed to by C5 in the merge example. There is no difference in the end product of the integration, but rebasing makes for a cleaner history. If you examine the log of a rebased branch, it looks like a linear history: it appears that all the work happened in series, even when it originally happened in parallel.

Often, you’ll do this to make sure your commits apply cleanly on a remote branch – perhaps in a project to which you’re trying to contribute but that you don’t maintain. In this case, you’d do your work in a branch and then rebase your work onto origin/master when you were ready to submit your patches to the main project. That way, the maintainer doesn’t have to do any integration work – just a fast-forward or a clean apply.

Note that the snapshot pointed to by the final commit you end up with, whether it’s the last of the rebased commits for a rebase or the final merge commit after a merge, is the same snapshot – it’s only the history that is different. Rebasing replays changes from one line of work onto another in the order they were introduced, whereas merging takes the endpoints and merges them together.

More Interesting Rebases

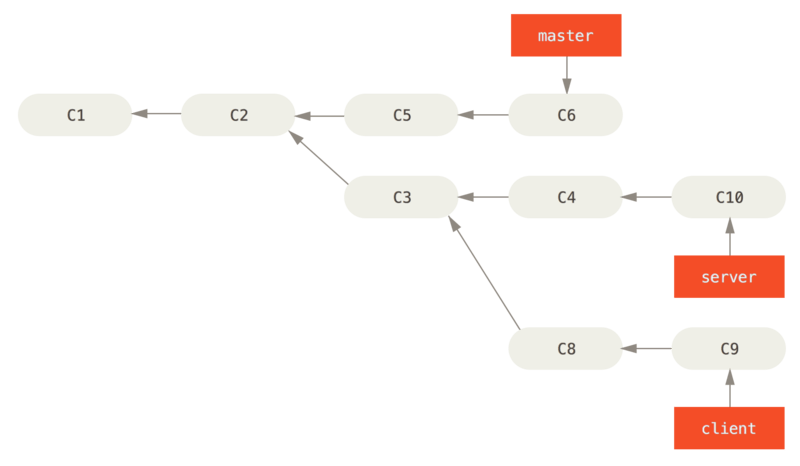

You can also have your rebase replay on something other than the rebase target branch. For example. You branched a topic branch (server) to add some server-side functionality to your project, and made a commit. Then, you branched off that to make the client-side changes (client) and committed a few times. Finally, you went back to your server branch and did a few more commits.

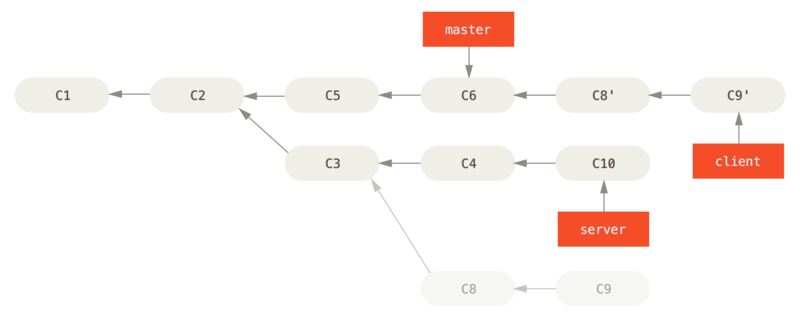

Suppose you decide that you want to merge your client-side changes into your mainline for a release, but you want to hold off on the server-side changes until it’s tested further. You can take the changes on client that aren’t on server (C8 and C9) and replay them on your master branch by using the –onto option of git rebase:

$ git rebase --onto master server client

This basically says, “Check out the client branch, figure out the patches from the common ancestor of the client and server branches, and then replay them onto master.” It’s a bit complex, but the result is pretty cool.

Now you can fast-forward your master branch:

$ git checkout master

$ git merge client

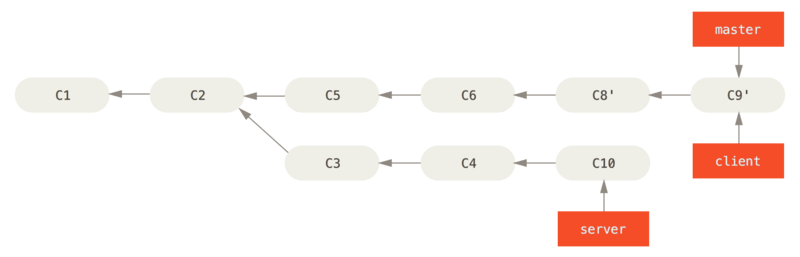

Let’s say you decide to pull in your server branch as well. You can rebase the server branch onto the master branch without having to check it out first by running git rebase [basebranch] [topicbranch] – which checks out the topic branch (in this case, server) for you and replays it onto the base branch (master):

$ git rebase master server

This replays your server work on top of your master work, as shown below:

Then, you can fast-forward the base branch (master):

$ git checkout master

$ git merge server

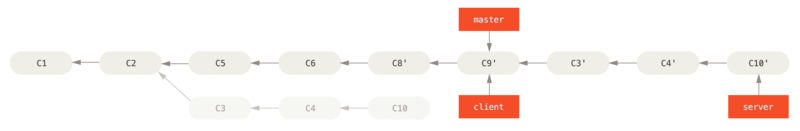

You can remove the client and server branches because all the work is integrated and you don’t need them anymore, leaving your history for this entire process looking like below:

$ git branch -d client

$ git branch -d server

Rebase vs. Merge

Now that you’ve seen rebasing and merging in action, you may be wondering which one is better. Before we can answer this, let’s step back a bit and talk about what history means.

One point of view on this is that your repository’s commit history is a record of what actually happened. It’s a historical document, valuable in its own right, and shouldn’t be tampered with. From this angle, changing the commit history is almost blasphemous; you’re lying about what actually transpired. So what if there was a messy series of merge commits? That’s how it happened, and the repository should preserve that for posterity.

The opposing point of view is that the commit history is the story of how your project was made. You wouldn’t publish the first draft of a book, and the manual for how to maintain your software deserves careful editing. This is the camp that uses tools like rebase and filter-branch to tell the story in the way that’s best for future readers.

Now, to the question of whether merging or rebasing is better: hopefully you’ll see that it’s not that simple. Git is a powerful tool, and allows you to do many things to and with your history, but every team and every project is different. Now that you know how both of these things work, it’s up to you to decide which one is best for your particular situation.

In general the way to get the best of both worlds is to rebase local changes you’ve made but haven’t shared yet before you push them in order to clean up your story, but never rebase anything you’ve pushed somewhere.